MUSIC FILMS FOR FANS

Curated Concerts, Artist Documentaries

& Exclusive Series

& Exclusive Series

$4.99/month with Amazon Prime account.

Cancel anytime.

THE STAGE IS SET

Stream hundreds of the most influential concerts, music documentaries, and episodic series all in one place.

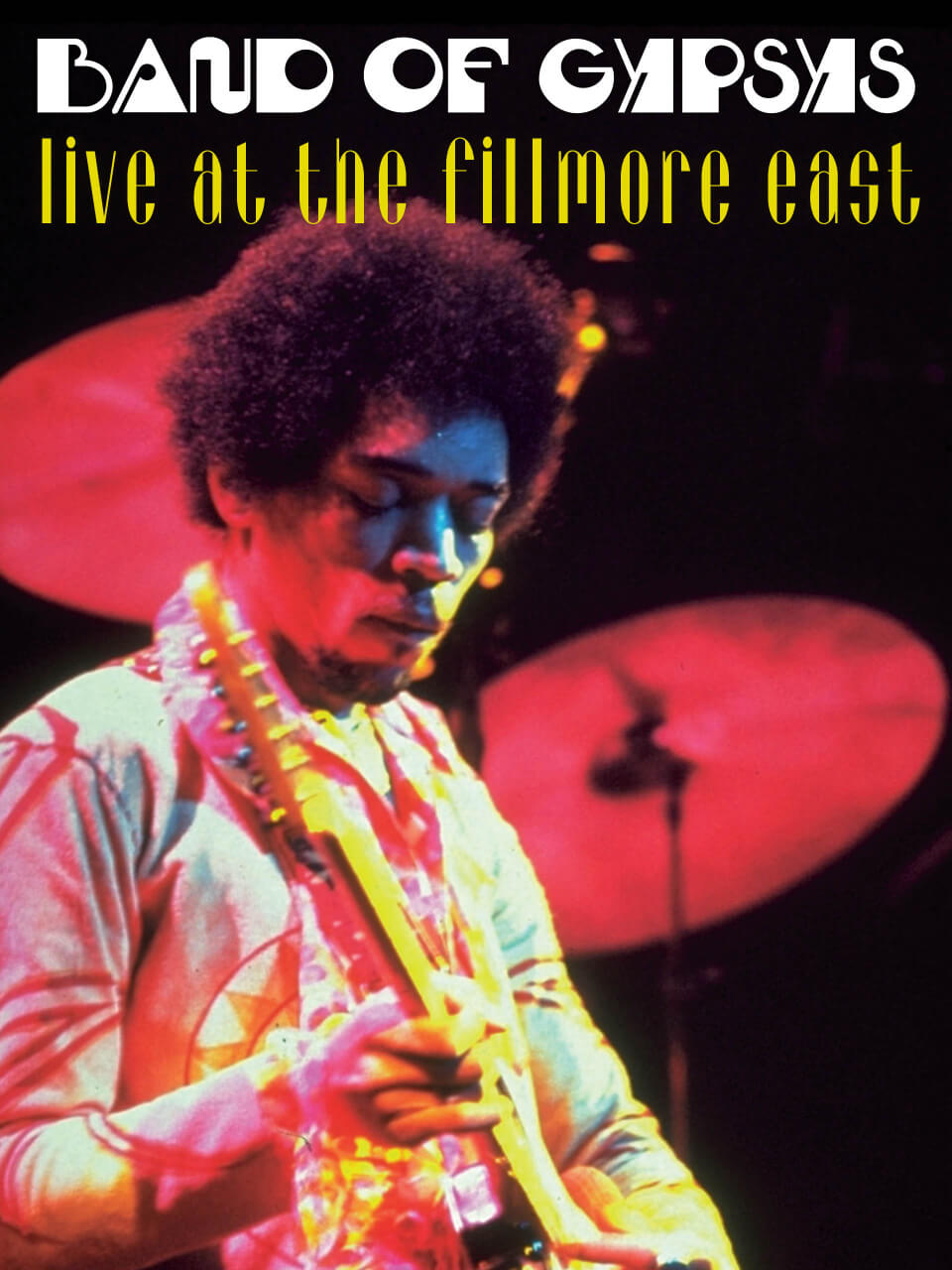

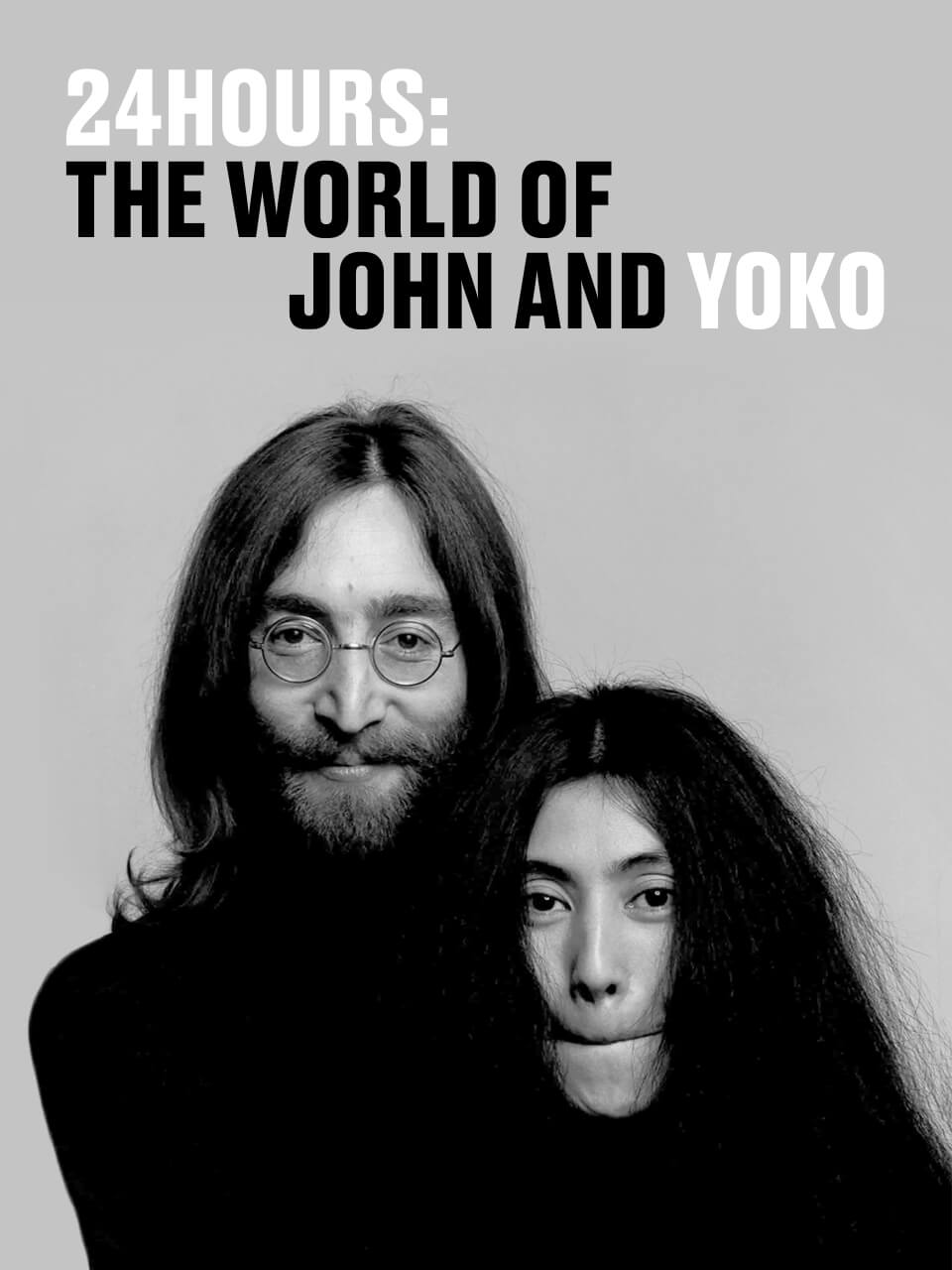

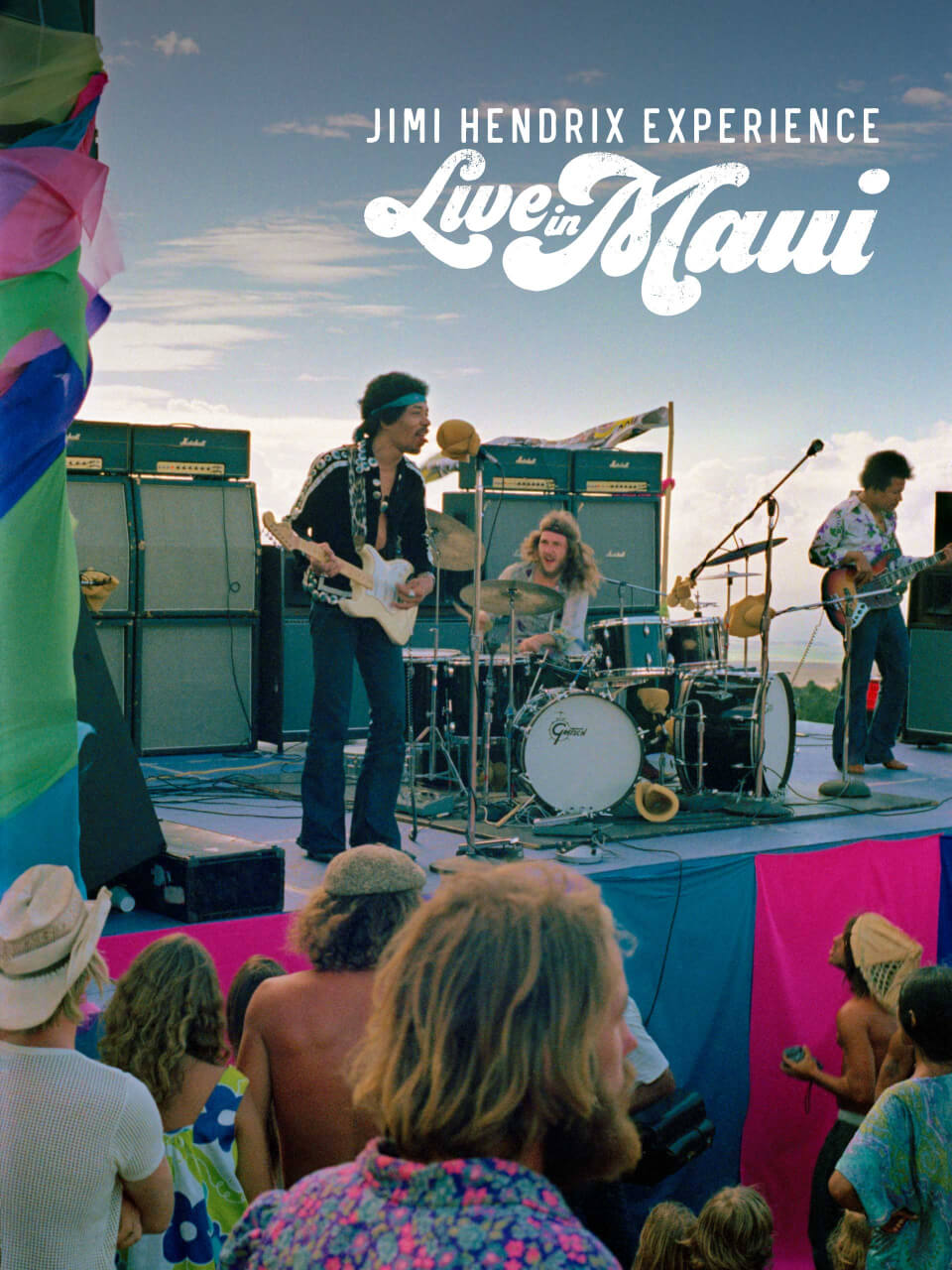

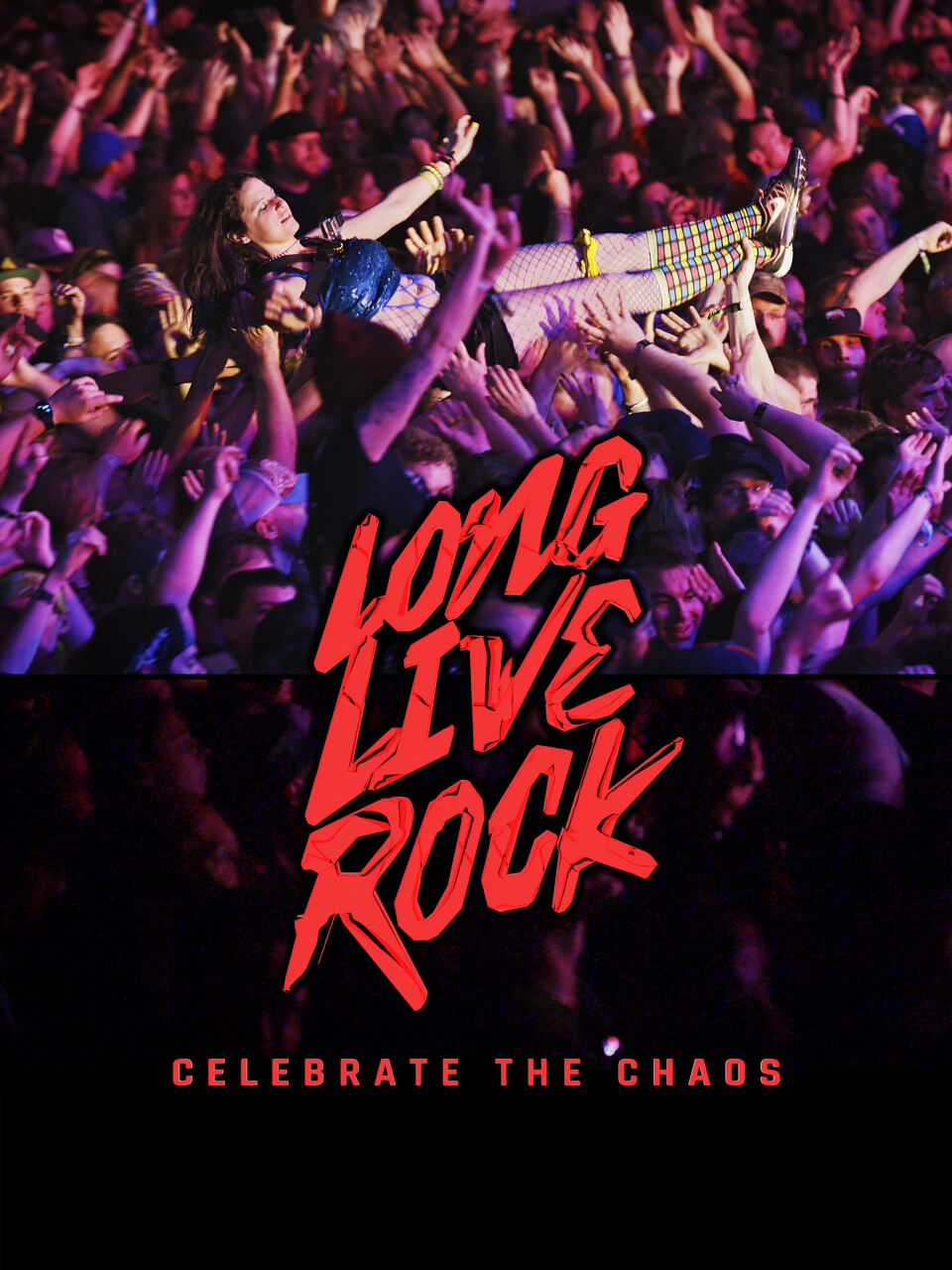

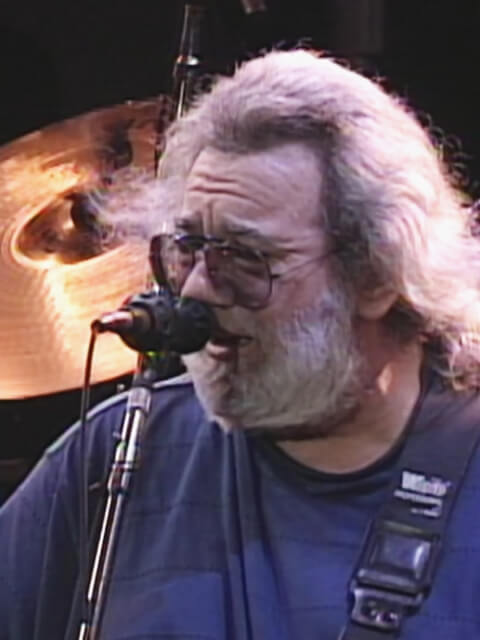

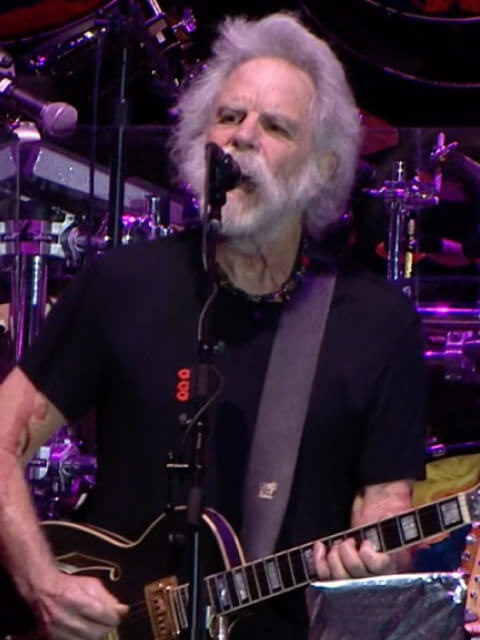

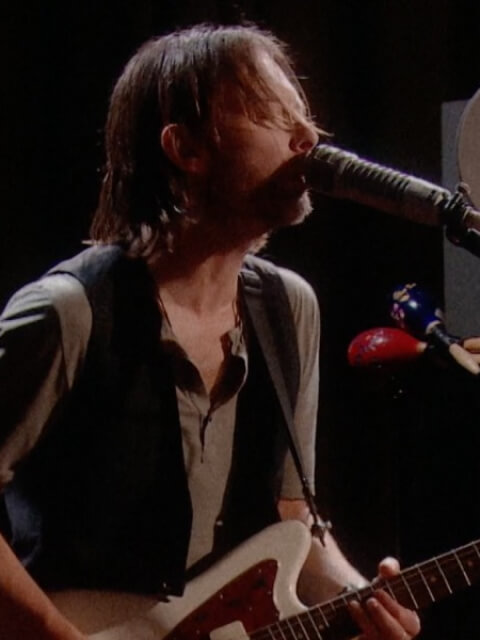

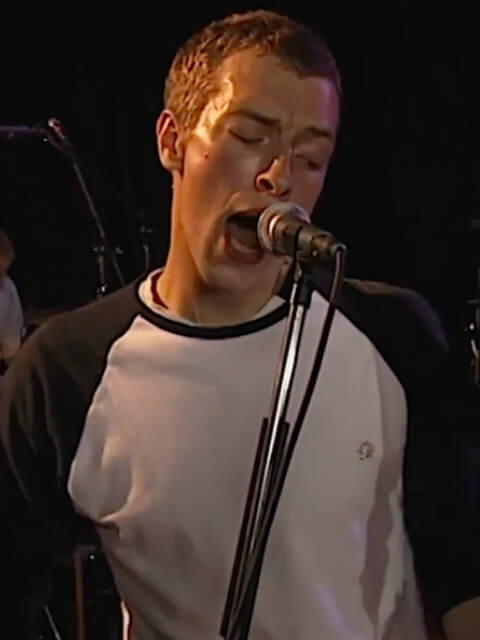

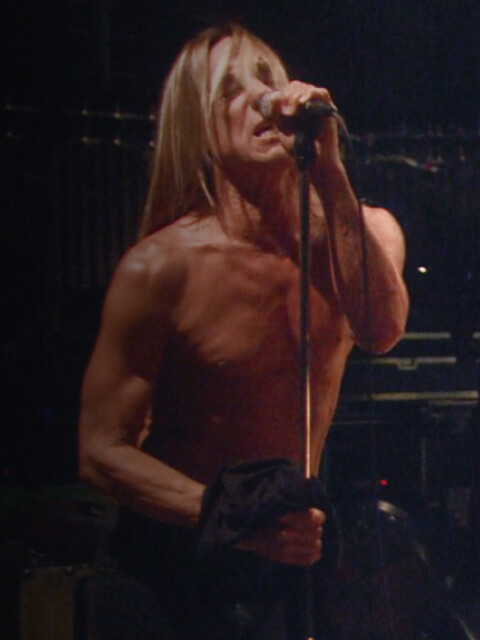

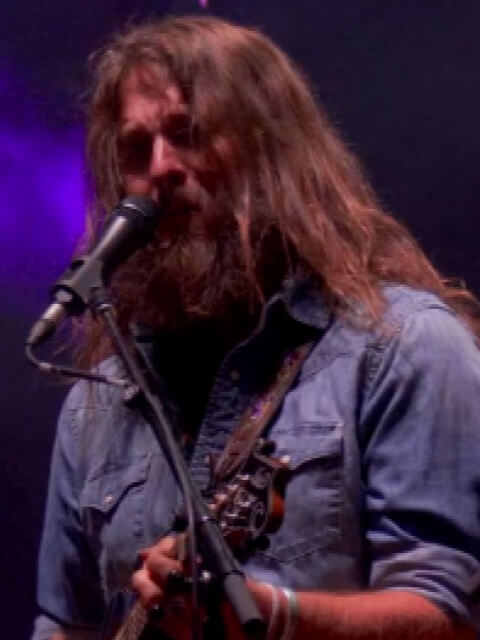

ICONIC PERFORMANCES

Step up to the front row of the most memorable moments in music, from intimate acoustic sets to electrifying stadium shows.

A HARMONIZED VIEWING EXPERIENCE

A song is just the start. Satisfy your love for music with deep insights, exclusive editorial, and interactive content without missing a beat.

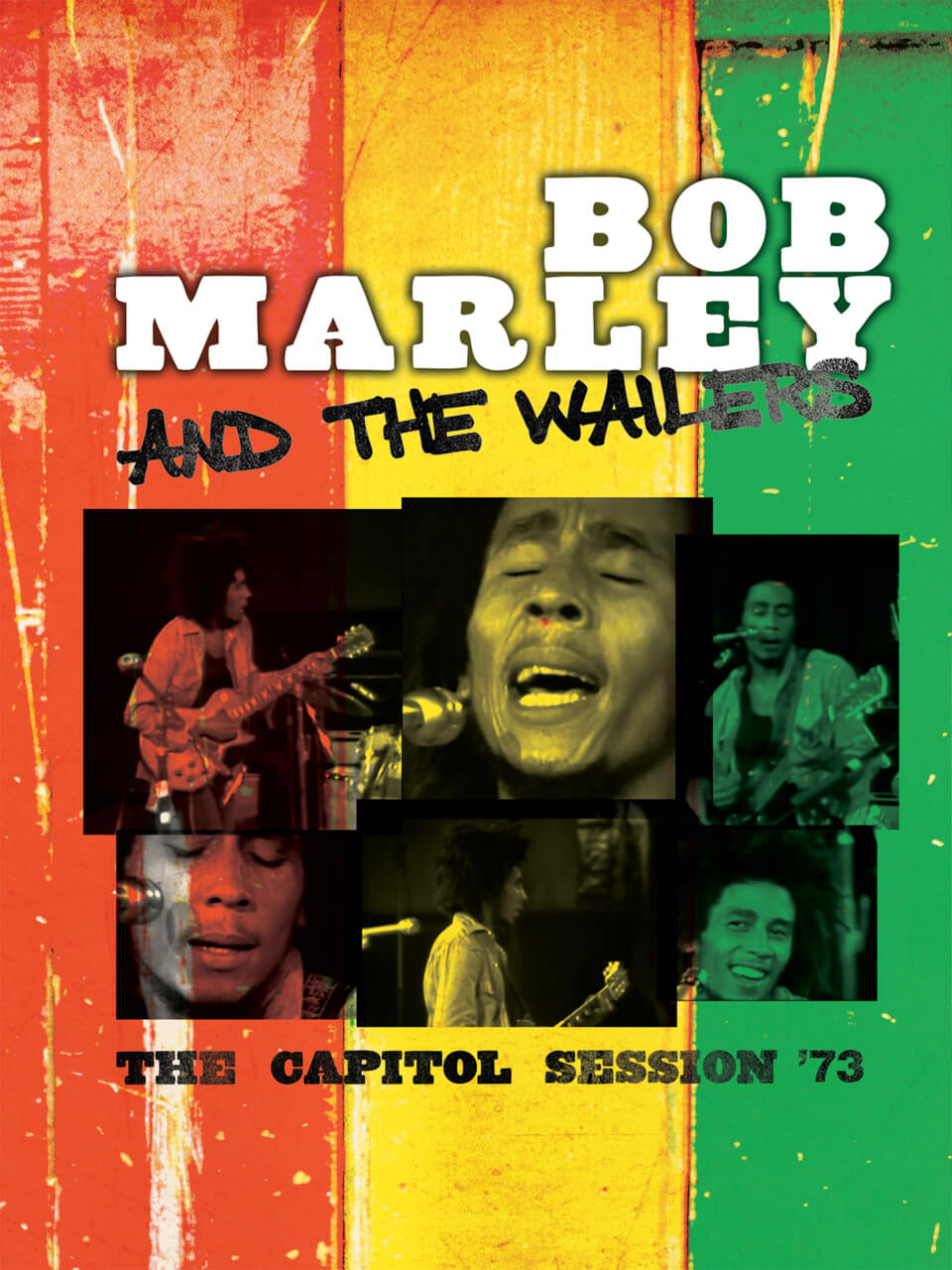

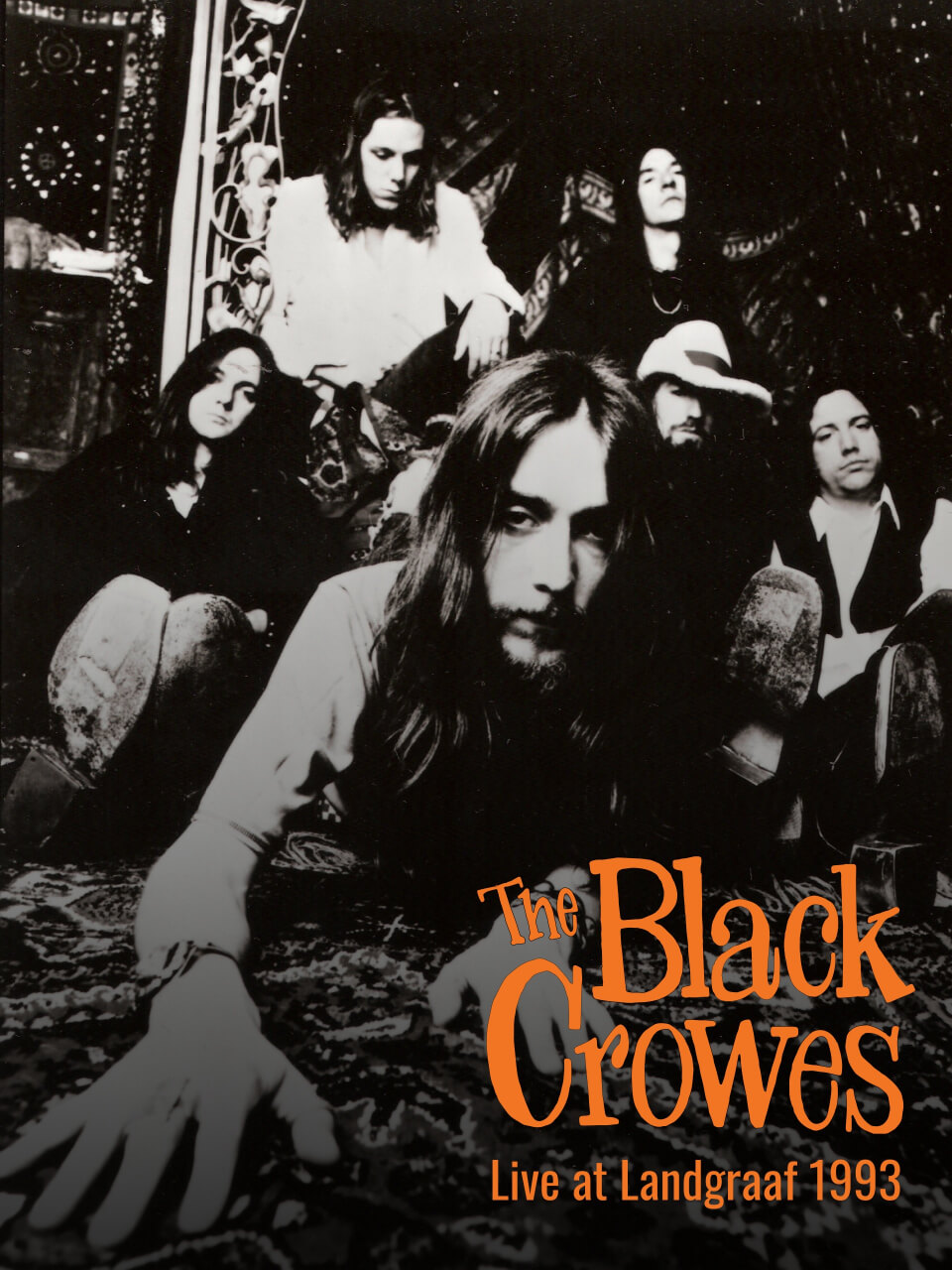

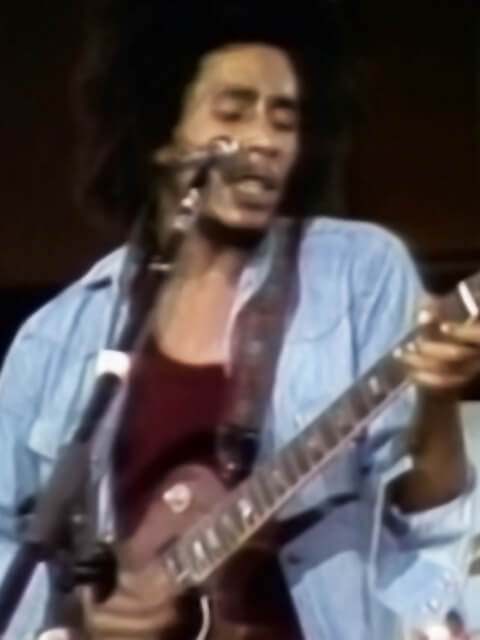

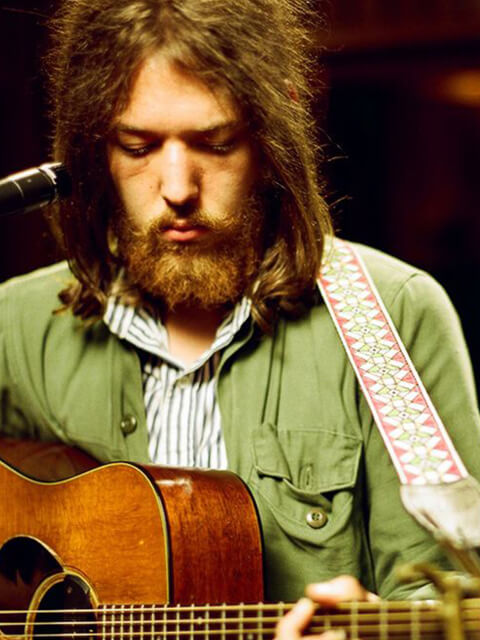

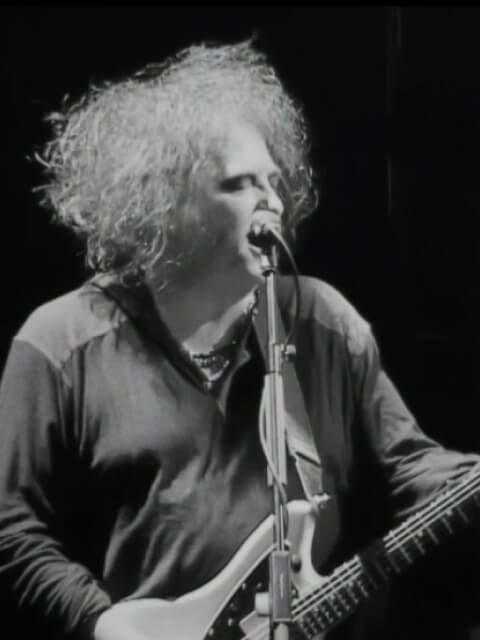

FROM THE VAULT

Dig through a deep collection of rare and exclusive films capturing history's greatest artists in unforgettable moments.

A HUMAN TOUCH

Break free from robotic algorithms and rediscover films and documentaries handpicked by passionate music fanatics.

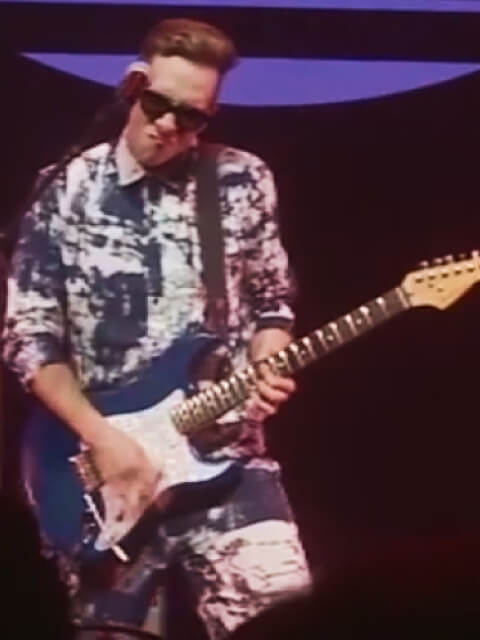

UNINTERRUPTED ORIGINAL QUALITY

Watch as the artists intended – no bothersome ads, cut-up setlists, or cellphone footage.

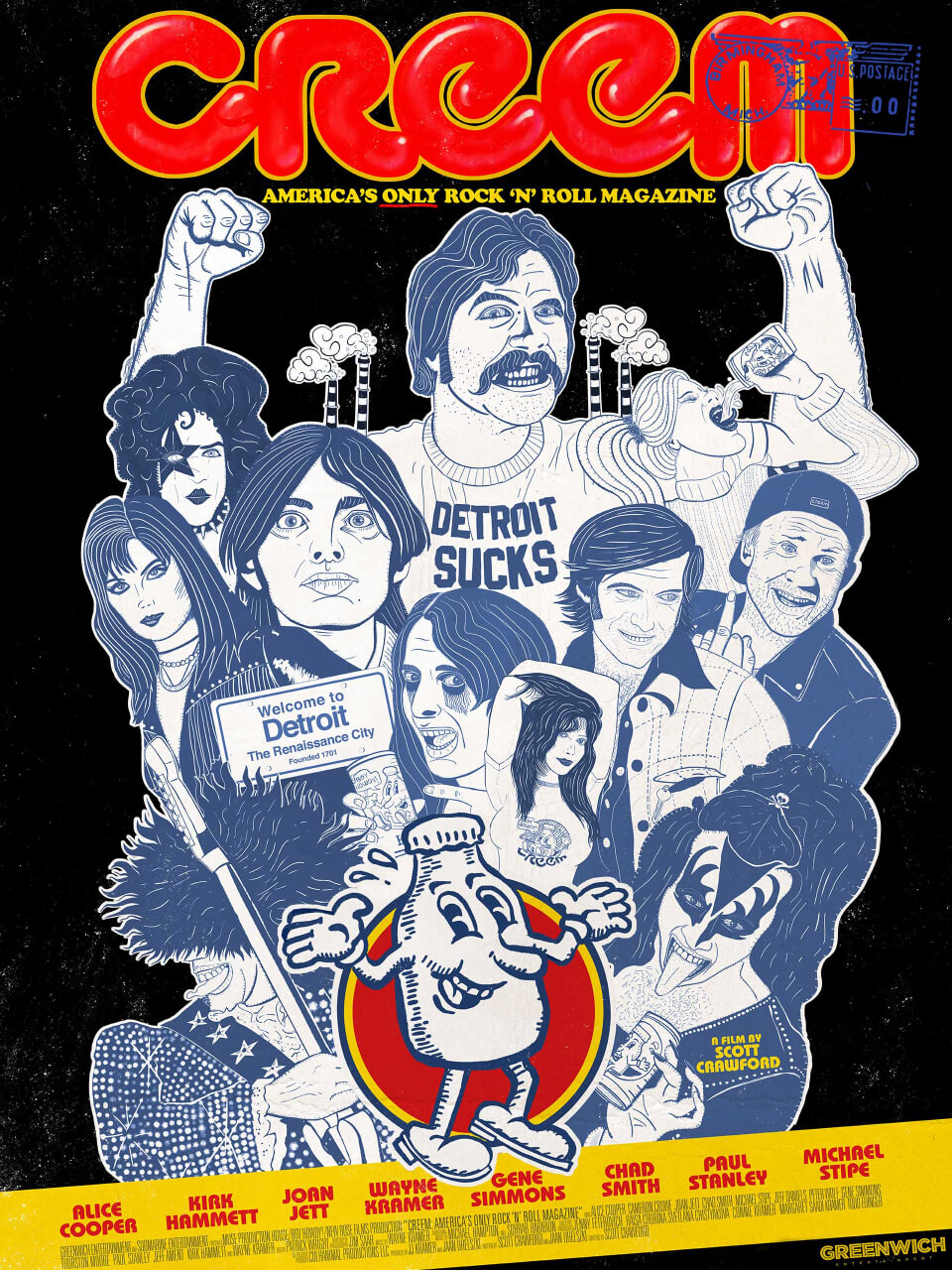

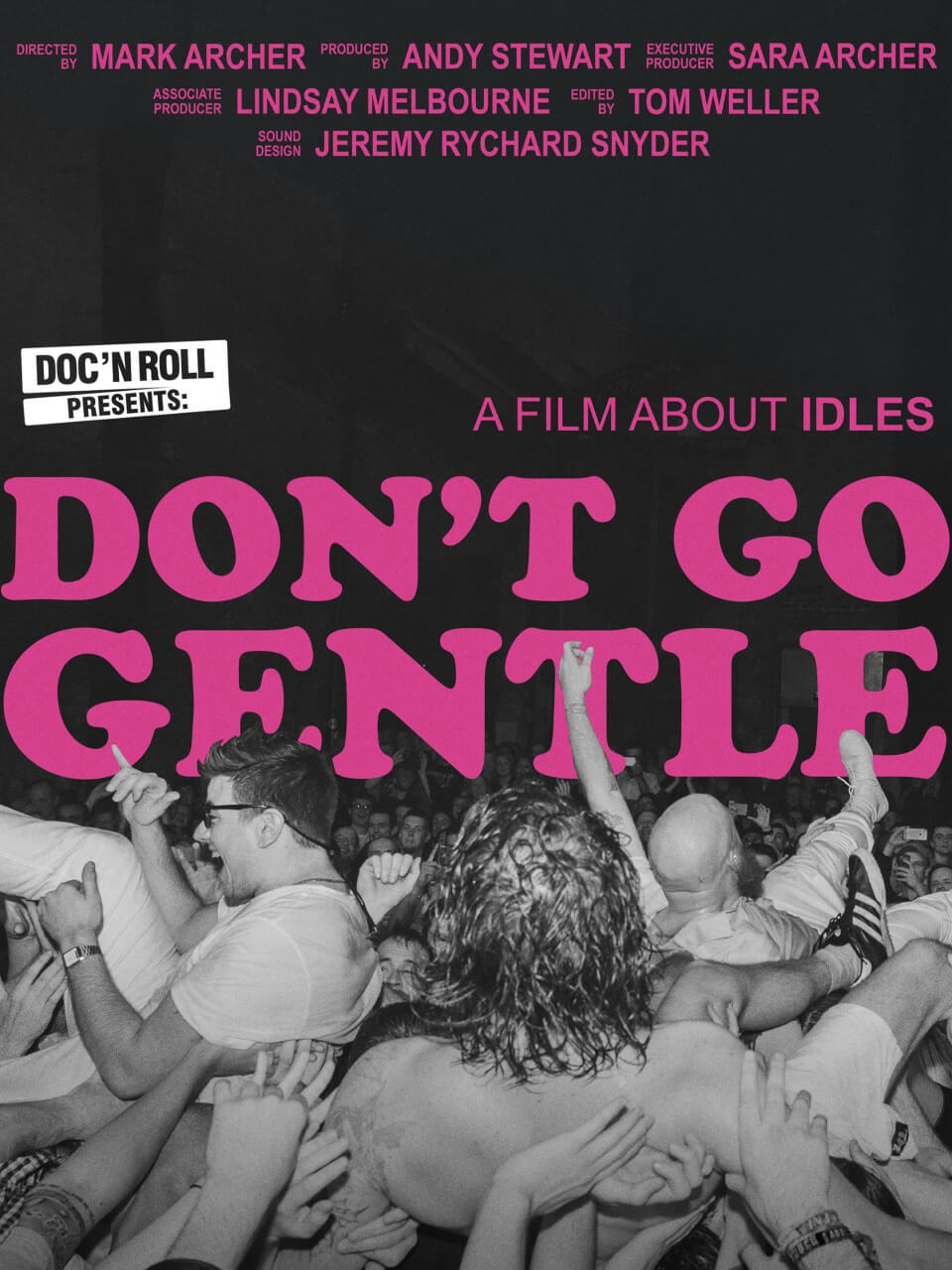

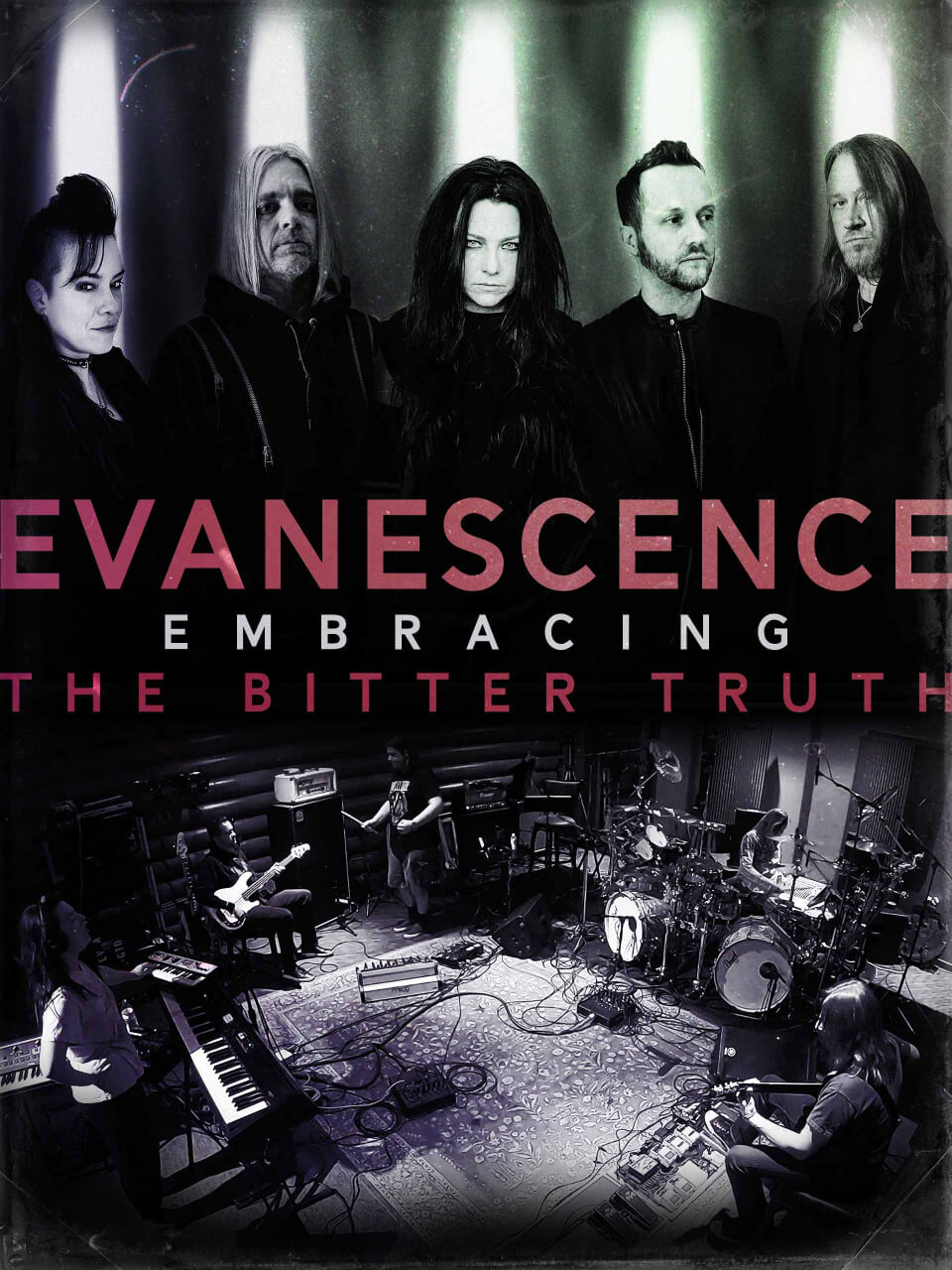

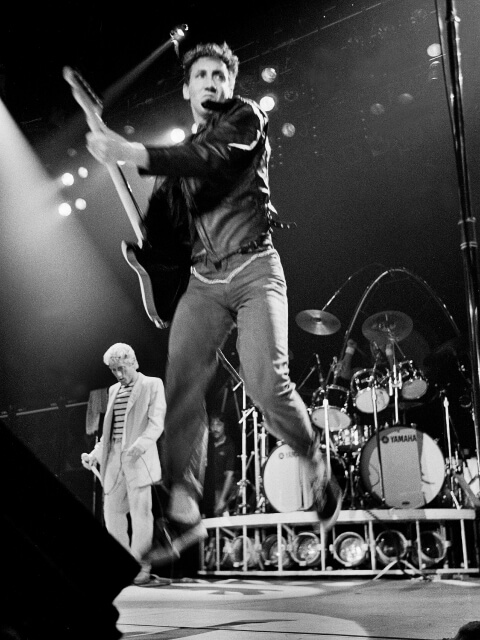

ROCKING'

DOCS

Go behind the music with unparalleled access to the lives and legacies of the icons who shaped the soundtracks of our lives.

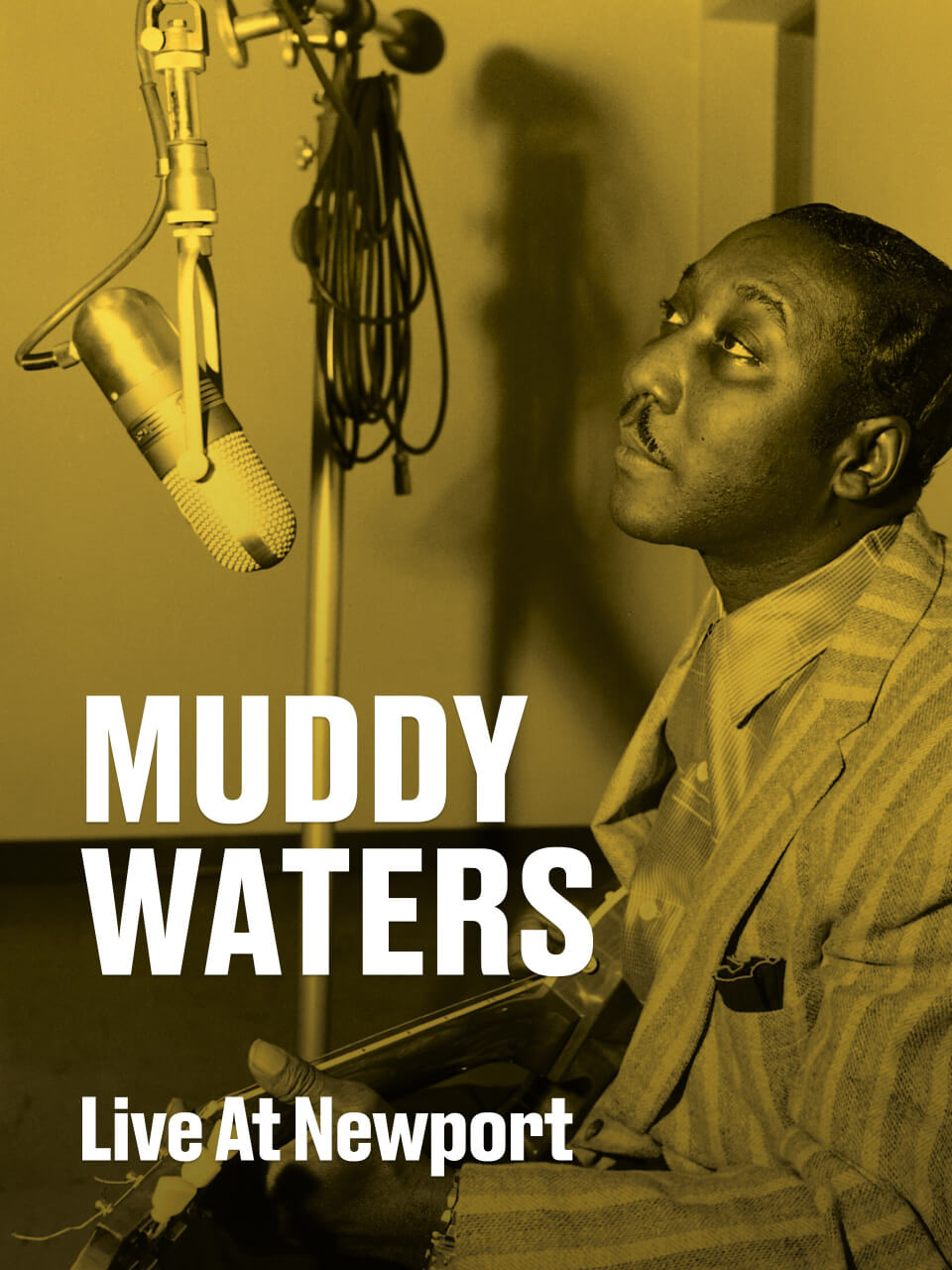

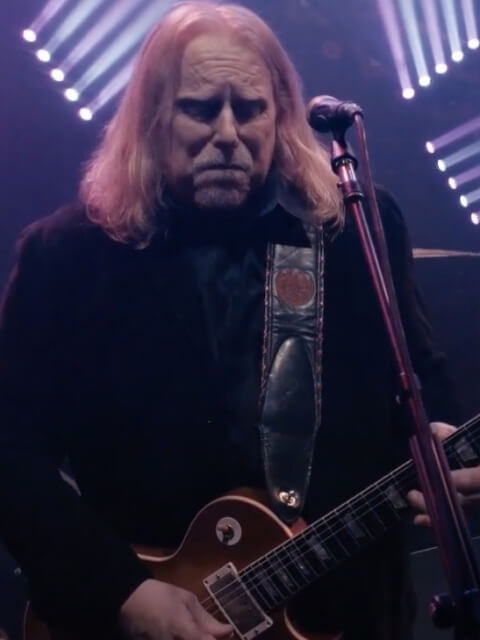

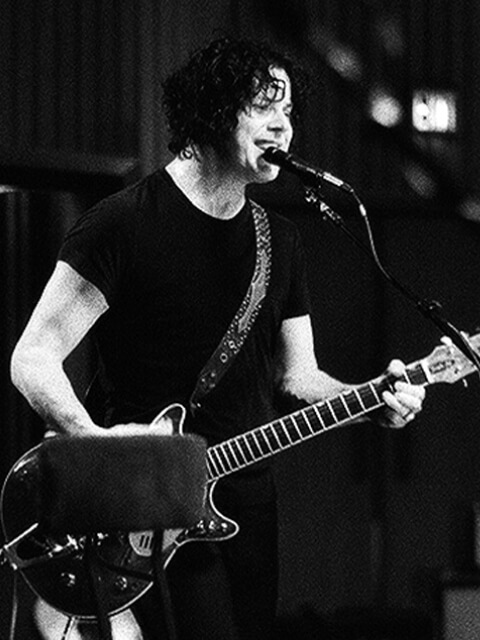

LEGENDARY LINEUP

Celebrate the timeless artists whose music shaped genres, defined eras, and inspired generations.

The Channel Music Deserves

The Coda Collection is available on Amazon Prime Video Channels. You can subscribe and stream on any device with the Amazon Prime Video app or website.

Nothing is Blocking Your View

Sign up and watch on your smartphone, tablet, Smart TV, laptop, or streaming device for one fixed monthly fee following the trial period.

Mobile

Tablet

Mac & Windows

Casting

Web

Frequenty Asked Questions

How much does the subscription cost?

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can I gift a Coda Collection subscription?

What countries is The Coda Collection available in?

Why is the video quality different for each release on the platform?

Where can I send a film request or inquire about hosting content?

Can I purchase the film on DVD/BlueRay or own it?